The orthodox view is that enhanced competitiveness should play a significant part in Ireland’s (and other euro area countries’) recovery from recession.

In the March 2012 “Review Under the Extended Arrangement” the IMF team states that:

“Ireland’s economy has shown a capacity for export-led growth, aided by significant progress in unwinding past competitiveness losses.” (my italics)

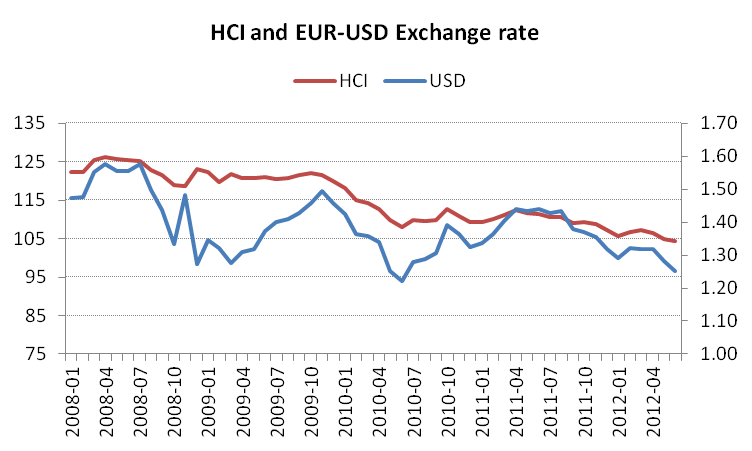

The evidence does indeed point to a significant improvement in Ireland’s competitiveness between 2008 and the present. The following two graphs show the ECB’s ‘Harmonized Competitiveness Indicator’ (HCI) based on (a) Consumer Prices and (b) Unit Labour Costs. (A rising index implies a loss of competitiveness.) Both graphs show a competitive gain since 2008, with second showing the more dramatic improvement. However, this measure is affected by the changing composition of the labour force, which became smaller but more high-tech as a result of the collapse of many low-productivity sectors during the recession.

Concentrating on the HCI based on the CPI, the Irish competitive gain has still been impressive – our HCI fell 17% between mid-2008 and mid-2012, giving us the largest competitive gain recorded in any of the 17 euro-area countries over these years. Greece, at the other extreme, recorded no change in its HCI, Portugal fell only 4.5%, Spain 6.6%, Italy 6.8%. So by this measure Ireland is some PIIG(S)!

However, we need to dig deeper and understand why Ireland’s HCI has fallen so steeply.

Part of the story – the part on which some commentators dwell – is that early in the recession the Irish price level and Irish nominal wages fell. From a peak of 108 in 2008 the Irish Consumer Price Index fell to 100 in January 2010. But it has started to rise again – by mid-2012 it was back up to 105. The fall in the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices has been even less impressive – from a peak of 110 to a low of 105 and now rising back to its previous peak.

Wages are more important than prices as an index of competitiveness because price indices are influenced by indirect taxes and include many non-traded services and administered prices. But Irish nominal wages tell much the same story as the price indices. The index of hourly earnings in manufacturing peaked around 106 at the end of 2009 (2008 = 100) and then fell to a low of 102 in 2011, where it appears to have stabilized. Even in the construction sector, where employment collapsed in the wake of the building bust, wage rates declined only 6 per cent between 2008 and 2011.

Falling wages and prices are in line with what many commentators thought would happen after the surge in unemployment in 2008. Widely-publicized wage cuts in the private and public sectors were seen as part of the ‘internal devaluation’ needed to rescue the Irish economy from the recession. It was argued that this was the only way we could engineer a reduction in our real exchange rate given our commitment to the euro. (Paul Krugman likes to refer pejoratively to an ‘internal devaluation’ as simply ‘wage cuts’.)

However, the Irish wage and price deflation has not been very dramatic and seems to have stalled in 2011, even though the unemployment rate continues to climb.

So why has Ireland’s competitiveness improved so sharply since 2008 if the ‘internal devaluation’ has been so modest? The answer, of course, lies in the behaviour of the euro on world currency markets and the fact that non-euro area trade is much more important for Ireland than for any other member of the EMU.

This can be seen by looking at the HCI for the euro area as a whole. The euro area HCI fell from 100 in mid-2008 to 84.7 in mid-2012 – almost as big a fall as was recorded for Ireland and far higher than that recorded in any other euro area country.

The paradox that the euro area HCI has fallen much further than the average (however weighted) of the constituent EMU countries is explained by the fact that for each individual country the HCI is compiled using weights that reflect the structure of that country’s total international trade, but for the euro area as a whole the weights reflect the only the area’s trade with the non-euro world.

In its notes on the series the ECB draws attention to this:

“The purpose of harmonized competitiveness indicators (HCIs) is to provide consistent and comparable measures of euro area countries’ price and cost competitiveness that are also consistent with the real effective exchange rates (EERs) of the euro. The HCIs are constructed using the same methodology and data sources that are used for the euro EERs. While the HCI of a specific country takes into account both intra and extra-euro area trade, however, the euro EERs are based on extra-euro area trade only.” (my italics)

It is understandable that Ireland should show a large competitive gain by euro area standards as the euro declined on world markets after 2008 because non-euro area trade is far more important to Ireland than to any of the other 16 members of the EMU. A fall in the dollar value of the euro does nothing to make France more competitive relative to Germany, or Greece relative to either of them, but it does a lot for Ireland relative to its two most important trading partners – the UK and the US.

As a consequence, the decline in the value of the euro on world currency markets, and especially relative to sterling and the dollar, has had a much larger effect on our competitiveness than on that of any other euro area country.

The following graph shows the USD / EUR exchange rate and Ireland’s HCI since 2008. It does not take any econometrics to convince me that the main driving force behind Ireland’s competitive gain has been the weakness of the euro. Undoubtedly a more sophisticated treatment, including the euro-sterling and other exchange rates of importance to Ireland – duly weighted – would show an even closer co-movement.

This should alert us to the point that Ireland’s much-praised recent competitive gain has been due more to the weakening of the euro on the world currency markets than to domestic wage and price discipline.

No doubt it could also be shown that a significant amount of the loss of competitiveness in the years before 2008 was due to the strength of the euro.

The fault – and the blame – lay not with us but with the far-from-optimal currency arrangement under which we labour.

Continuing gains in competitiveness would therefore seem to depend more on further euro weakness than on the process of ‘internal devaluation’. Should this have been a condition of our Agreement with the Troika?

34 replies on “Regaining Competitiveness”

Shorter : mostly extra euro export economy needs weaker euro to export more

@Brendan.

Excellent piece. Very interesting.

@ Brendan Walsh

+ 1

However;

“The fault – and the blame – lay not with us but with the far-from-optimal currency arrangement under which we labour.”

We went into the euro eyes wide shut and have nobody to blame but ourselves.

@brendan

“Continuing gains in competitiveness would therefore seem to depend more on further euro weakness than on the process of ‘internal devaluation’. Should this have been a condition of our Agreement with the Troika?”

Not sure I follow. Are you suggesting that Ireland should have refused to access the Troika’s credit line unless they committed to weaken the Euro against a basket of trading competitors’ currencies?

If I have that right, do you think the Troika could in a reliable way tell the difference between action likely to get currency traders to sell as opposed to buy Euros based on experience thus far?

DOCM:

‘We went into the euro eyes wide shut….’

Really? The points made by Brendan Walsh about the Irish trade pattern, unique amongst the original Euro joiners, were made interminably by numerous people right through the 1990s. Dismissed by knowledgeable people including Bertie, who opined that the UK would join in due course!

@ CMc

I was referring to those who took the decision and the wide level of public support for the step.

I readily concede that there were numerous (?) voices, your own included, that voiced serious misgivings. But our mistakes are our own.

@ CMc

On reflection, I may be overdoing it in referring to a wide level of public support. In retrospect, most people voting to ratify Maastricht were unaware of the fact that they were also signing up to the euro.

Incidentally, I think Bertie will be proven to be correct. (I may be giving a hostage to fortune there).

It is a very good thing that Ireland is gaining competitiveness ,but the low competitiveness was an effect ,not a cause , the huge housing and credit bubble , due to the much too low interest rates was the main problem .Having regain competitiveness is going to help the deleveraging ,but this is going to be a very long process nevertheless .The Troika has been acting as if Ireland was Greece or Portugal ,because it is difficult to say ,”you just have to wait until those crummy mortgages are paid off and your banks are recapitalized” .

DOCM,

Ever hear of divorce? Or is the Euro like Catholic marriage from the time of John Charles McQuaid?

The point is probably moot at this stage. The battle for Spain is over, the battle for Italy has begun and the battle for France will follow.

@ Tull

A single currency, believe it or not, has many advantages!

Off topic…or maybe not

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/health/2012/0724/1224320699772.html

How did we arrive at the situation thar the State is responsible for the negligence of others to the tune of 130 million euro.

Off topic…or maybe not

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/health/2012/0724/1224320699772.html

How did we arrive at the situation thar the State is responsible for the negligence of others to the tune of 130 million euro.

DOCM,

A system as ineptly run as the EZ does not deserve to survive. Other systems based on outdated flawed logic have collapsed, take for example the USSR.

@ Tull

I made no claims with regard to the euro. I was simply making the point that a single currency in closely intergrated economic area – such as Europe – has many advantages. Whether the euro deserves to survive or not is neither here nor there. My own view is that the political and economic imperatives are such that it will.

The USSR provides a model for nothing whatsoever.

We should demand a Commerzbank Arena Agreement on the euro to match our own CPA’s effect on competitiveness.

DoCM,

You doth protest too much. The EZ is hardly integrated at all. The labour Market is balkanised. The banking system has become balkanised. It is not obvious that a Spanish euro is the same as the German euro-people seem not to want the former. The EZ has no central bank in the conventional sense.

The parallel with the USSR is the imposition of a vision from the top with sufficient consent from the bottom. Voters have usually voted against integration but this has not stooped the europhiles from carrying on with their vision. Best the whole ramshackle edifice collapse.

@docm

Bertie has been wrong about the UK following suite with its tail between its legs by joining the Euro for substantially more than a decade. Unless you are falling in behind him on the basis that 50 years hence the UK might be part of a very different ‘Euro’ then I suspect you and your trolley have parted company, the trolley sneaking off in a mysterious, not wanting to be found sort of way…..

@Tull and DOCM

Tull,, you are right. DOCM you are wrong.

Tull

So you are a Austrian. Or what?

@Brendan Walsh

Great piece but sorry to burst the bubble Constantin Gurdgiev has been making the very point that you examine here periodically over the past 2 years i.e. the internal devalution in Ireland ex the currency effect have been quite marginal relative to where we were at. The Croke Park arrangement has ensured, on the Public Service side of the house at any rate , the current status quo will do nicely and further wage cuts are unlikely. Time will tell here I fear.

The primary reason for the apparent cessation in wage cuts is likely twofold 1. the euro devaluation has done the work for us (as noted) and 2. mortgages.

Those who have lost jobs are not fit to service their home loans and are already in a default process and those with jobs can’t afford to take any further cuts otherwise the arrears numbers go to the moon. So the euro devaluation is oddly, providing an escape clause for a real mortgage arrears armageddon. Strange I know, but on this analysis seemingly true.

If the euro survives and that’s a rather large if, the trend in ECB base rates will likely rise and the recent euro devaluation will likely reverse. On both counts this represents a dire mix for Ireland Inc. into the future. Higher mortgage rates and likely wage cuts, which the devaluation has deferred, will present ongoing and lasting difficulties for an overly indebted consumer. There’s no getting away from it – domestically based economic growth is really a pipe dream until the banks and Govts wake up to the fact that debt write offs are the only real solution. Its been said here and elsewhere a thousand times but worth repeating – until losses on dire bank lending decisions are taken by either bond, deposit or other bank financiers including the likes of the ECB/EFSF/IMF etc etc we go nowhere.

I assume Irish policy makers were somewhat influenced by US companies regarding the adoption of the euro, because of the single market.

However, FDI in fact peaked in 1999 and anyone who has prepared accounts in a US subsidiary, which I have done myself, will know that most of the inputs are in dollars as are the outputs.

Irish factory gate prices closely track changes in the USD/EUR rate.

As for wages, I’m not surprised that levels did not fall significantly.

My experience in industry in the 1980s was that if possible, a restructuring should be done once and the pay of remaining staff should be either increased or performance pay should give workers a reasonable chance of increasing their earnings.

On competitiveness, we do have miracle workers and about 49,000 direct staff accounted for 69% of total Irish exports (goods and services) in 2011 – – 2.33% of the total workforce including the unemployed.

A real rise in competitiveness through a fall in the euro, has helped some indigenous companies selling in the UK.

However, currency changes for FDI firms selling into global supply chains do not matter in the short to medium term. Besides, the Irish based ones report high profits.

Of course politicians and some others use competitiveness as a convenient spin and it’s interesting to wonder how would Glanbia, Ireland’s biggest dairy company, take advantage of it.

Glanbia is not among the world’s top 20 dairy companies and 6% of its sales come from the UK, 10% from the rest of Europe and 42% from the US.

In 2003, a report by two firms of consultants, Prospectus and Promar International, proposed a merger of 3 of the top 5 Irish processors – – Kerry, Glanbia and Dairygold – – to create a single consolidated player processing in excess of 70% of the milk produced by 2008.

Apart from focusing on the need for increased scale at both production and processing levels, the consultants urged a major change in the product mix being produced by the Irish dairy industry – – away from commodity type products and into higher value added products.

“The Irish dairy industry produces over 60% of its output in the form of base or commodity type products (butter, powder, casein and bulk cheese),” the report said.

“These products attract lower margins and are extremely price sensitive. The industry relies heavily on EU market intervention and other market supports that are increasingly coming under threat. It has developed very few internationally branded consumer products.”

It’s likely that linkages to the home market would be stronger if it had concentrated on markets in Europe rather than buying cheese factories in the US. Arla, the Danish-Swedish cooperative for example has a strong position in many markets.

Arla is four times the size of Glanbia and by 2015 has plans to be No. 1 in the UK (2); No. 1 in Denmark (1); No. 1 in Sweden (1); No. 2 in Finland (2); No. 2 Netherlands (2) and No. 3 in Germany (7) — current rank in brackets.

Very interesting read.

@ Tull et al

I agree, of course, that Europe is far from being integrated in the manner that the US is. However, in relation to the trade in goods, which is the significant area in which a single currency can be of particular benefit, it is.

I find it difficult to imagine the EU abandoning the euro. It is for this reason that I think that it will ultimately prevail. This will leave the UK as odd man out.

The error as far as Ireland is concerned was not in joining the euro but in doing so without the UK, given the pattern of our trading links with it, and the extent of our non-EA trade, as demonstrated in this post by Brendan Walsh.

DOCM,

The EU may not abandon the euro but some of its members look like they will. What if German policy all along was to drive the weakest out and re-fashion it as a strong smaller more integrated reserve currency?

@ Tull

What if, indeed! It seems to be the policy of the FDP at least.

One way or the other, Germans of all parties regret the error of allowing Greece to join in the first place.

I’m afraid this is a very interesting but depressing post – given that we have very little control of the exchange rate and that some of our big exporters may be facing various walls that we also have no control over (e.g patients on pharmaceuticals).

Can we get over the idea that wages fall in a recession? Its a bit of neoclassical thinking that has proved time and time again to be wrong. Typically firms lay off peripheral workers (part-time, contract, non-core) so its average wage bill increases even if its total wage bill is declining.

If you ran an IT company in trouble would you sack the cleaner or the programmer? And what would that do for your average wages?

@ DOCM

I just wonder how important the trade destination argument is.

In 2011 Germany exported 40% of its goods shipments to the EMU and Ireland’s ratio was 39%.

Ireland’s services ratio was 40% in 2010.

Germany’s services deficit was €31bn. I haven’t got a location breakdown of the exports.

One important trade fact is that indigenous companies did not take advantage of developing exports in non-English speaking European countries.

Enterprise Ireland said three years ago that the markets, Germany, France, Benelux, Italy and Spain, collectively represent a GDP 3.9 times the size of the UK, yet the non-food exports by clients companies of the agency for these countries, was 40% of that of the UK.

The downward wage stickiness, particularly in construction, is impressive in a depressing kind of way. Truman Bewley’s work comes to mind.

http://www.amazon.com/Wages-Dont-Fall-during-Recession/dp/0674009436

Most of Irelands exports are in reality re-exports. Cimpetitiveness is difficult to quantify given the level of transfer pricing.

Most of Irelands exports are in reality re-exports. Cimpetitiveness is difficult to quantify given the level of transfer pricing.

@ MH

I do not think that it is that important. Much more significant is the skewed make-up of Irish exports because of the dominant FDI element to which you have rightly and repeatedly drawn attention. You make the point indirectly in your second post i.e. for most indigenous Irish exporters, the world stops at Dover. This is simply a reflection of the close integration of the UK and Irish economies which is hardly a major discovery. It seemed, nevertheless, to have escaped the attention of policymakers when we joined the euro.

@Brendan Walsh

Useful.

Let’s take a look at how the cake is distributed …

In a previous post we looked at how our rich are richer than the rich of other European countries. Our rich grab a higher proportion of disposable income. That’s one side of the coin. Let’s look at the other side: that our ‘poor’ take a lower proportion of disposable income than the poor of other countries. This issue, finally, is gaining some currency. Social Justice Ireland has pointed out that inequality in Ireland is rising under current Government policy, while Vincent Browne wrote on the same theme yesterday.

In every decile in the lower half, the take of national income is less than the EU-average (for an explanation of equivalised income, see the post on high incomes). The difference in the numbers may seem merely fractional, but they add up at the national economic level (and don’t forget – the top decile, the top 10 percent, take over 26 percent of all national income).

http://www.irishleftreview.org/2012/07/16/raising-floor/

Follow the links to see distribution for upper deciles ….

@Brendan

A recent article by Constantin Gurdgiev on a similar vein

http://trueeconomics.blogspot.ie/2012/07/2972012-irish-competitiveness.html